Guest: Dr. Eilat Mazar

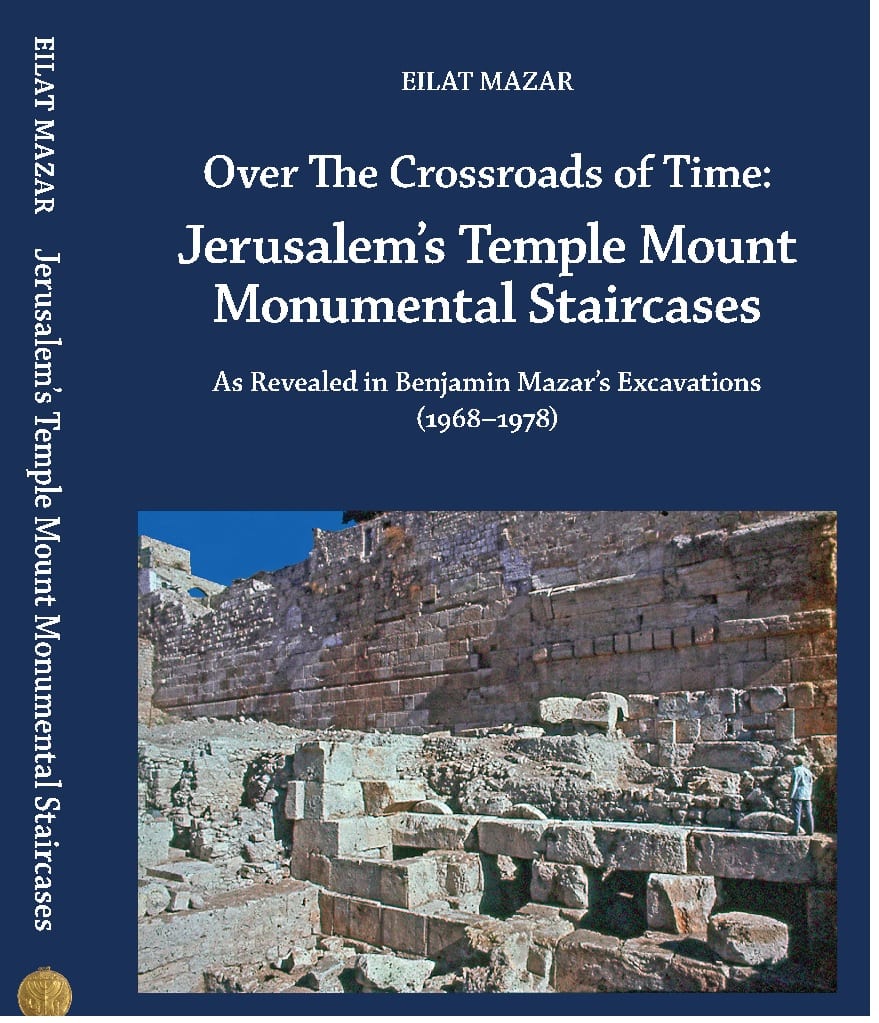

It has recently come to light that the Second Temple period remains that were uncovered in the excavations at the foot of the Temple Mount walls are, in fact, large crossroads that led directly to the Temple and to the Royal Stoa on the Temple Mount.

Dr. Eilat Mazar, from the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, announced the results of the research she has conducted in recent years. This research clearly shows that the remains unearthed by her grandfather, Prof. Benjamin Mazar, in the excavations that he conducted on behalf of the Hebrew University half a century ago are the largest and most sophisticated crossroads known to classical architecture.

In the eighteenth year of King Herod’s reign (19 BCE), the he began the tremendous construction project on the Temple Mount that continued until his death. He initiated a new master plan that doubled the area of the Temple Mount compound (to about 36 acres), containing the reconstruction of the Temple in its center, as well as completely new construction – the magnificent Royal Stoa (basilica) that extended along the entire inner length of the compound’s Southern Wall (282 m). These structures represent the high point of classical architecture, in terms of their size, power, and beauty.

Since the Temple, on the one hand, and the Royal Stoa, on the other, essentially differ – the one, wholly sacred, and the other, entirely mundane – separate access routes had to be built, employing large staircases in various directions.

The archaeological excavations that Prof. Benjamin Mazar conducted at the foot of the Temple Mount during the years 1968-1978 uncovered the large crossroads built by Herod that were used by the thousands of pilgrims and visitors to the Temple Mount, without fear of the intermingling of sacred and mundane, the ritually pure and the unclean. The archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar is publishing for the first time the story of the excavations and the surprising discovery of the great crossroads, as they came to light in the processing of the finds from these excavations, and which the excavators themselves could not comprehend without the perspective of time.

Five volumes of the finds from the Benjamin Mazar excavations at the foot of the Temple Mount walls have already been published in the QEDEM series of the Hebrew University’s Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology. The results of the excavations of the crossroads there will be published in the sixth volume of the series. For many years the publication project led by Dr. Eilat Mazar has been generously supported by Roger and Susan Hertog of New York. The Philadelphia Church of God, led by Gerald Flurry, is aiding the publication project, thereby continuing in the footsteps of the Church’s founder, Herbert W. Armstrong, who supported the excavations from their beginning.

Herod built the great crossroad structures great crossroad, one of a sacred nature, and the other, mundane, as part of the master plan: at the foot of the Southern Wall he erected the Three-Way Staircase (282 X 22.5 m) that led straightaway from the dozens of mikva’ot (ritual baths) below the walls to the Temple, and the Four-Way Staircase (55 X 50 m) at the foot of the southern end of the Western Wall, that directly connected the Royal Stoa with the Upper City to the west, with the suburbs and the Herodian Street in the Tyropean Ravine, and with the City of David to the south. The size and sophistication of these crossroads are unparalleled in classical architecture.

The rooms of the Four-Way Staircase contain rock-cut ritual baths and hundreds of finds from the Second Temple period until the Destruction in 70 CE. These finds include pottery vessels, stone vessels (that do not acquire ritual impurity), coins, and weights used by the masses who came to the Temple Mount.

Herod succeeded in finishing the construction of the great crossroads before his death in 4 BCE, while the building of the streets, plazas, and shops around the compound would be in abeyance for another forty years, until the time of the Roman procurator Pontius Pilate (26-36 CE), and mainly, that of Agrippa I (41-44 CE), the last Judean king and the grandson of Herod and Mariamne the Hasmonean. It was only then that the final phase of the comprehensive construction around the compound and the great crossroads was completed.

The Benjamin Mazar excavations uncovered shops and paved plazas and streets that belong to the final phase of the construction plan.

One of the vaulted rooms of the plaza adjoining the Four-Way Staircase yielded a cache of bronze coins bearing the inscriptions, in Paleo-Hebrew script: “Year Four” (the year 69 CE) and “For the Redemption of Zion.” Immediately following this date the Romans conquered Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple and its surroundings. These then were newly minted, and uncirculated, coins.

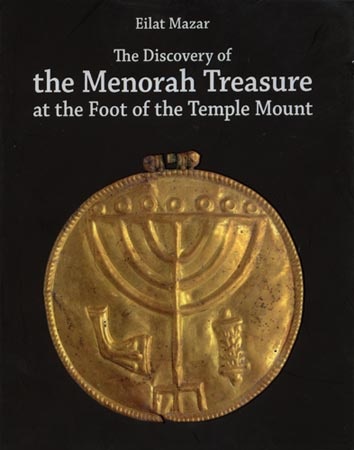

The adjacent vaulted room contained a small gold ring (less than 1 cm) that was apparently intended for a newborn child, bearing an engraved stalk with seven branches resembling the Seven-Branched Menorah that stood in the Temple.

The discovery of the great crossroads shed new light upon the Herodian construction enterprise on the Temple Mount and its surroundings, and showcase the new high point of classical architecture that only Herod’s vision and genius could have conceived. With migh and magnificence, his vision combined the values of the Jewish people and religion with those of the surrounding world, and led them to heights unparalleled to the present day.