[su_vimeo url=”https://vimeo.com/276950414″]

A

B

C

D

E

TRANSCRIPT

(START RECORDING 00:00:00)

Rabbi Alter Bukiet: Good morning, everybody. So we’re going to start a class now, a little late, but we’re going to start the class. Just to remind you that next week we’re not going to be doing the class, so this class is this week, we’ll pick it up in two weeks from now, G d willing. Back to our class and the Rebbe’s vision.

So I want to start this class, because this is an important subject in the Rebbe’s world. Let me explain to you why, on a very personal level. I one time heard from the Rebbe’s secretary, Rabbi Krinsky. Rabbi Krinsky, one time said at a Chassidic gathering. He said that the Rebbe once told him that there was a major difference between me and my father in law the previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn. The Rebbe said, my father in law, by nature, was a marah levanah. Translation? Outgoing and happy. He worked on himself to be restrained, to be more disciplined, to be a little bit of a marah shechorah. A little bit of someone who controls their emotions and restrains himself.

The Rebbe said I’m the opposite. By nature, I’m a marah shechorah. I’m a person who’s very restrained and to a certain level, has embitterment in his life. Which was self understood, without any major explanations. The Rebbe lived a very internal life and struggled in many things in his life. I work very hard on being happy. That’s a work of my life, of bringing joy into my life.

The Rebbe, when the return of the books happened in 1987 the Rebbe’s library was returned to him. When they finally closed all the court cases that were involved and it was finalized and it was complete the whole story. The Rebbe said to Rabbi Krinsky and Rabbi Shemtov, when they walked into him and gave him the closure documents from the court. The Rebbe said is this it? They said, yes, this is it. The Rebbe’s reaction was, he said, in my life nothing has come to me easy. People have been very jealous of things that have come to me and I have struggled for everything that I’ve gotten in my life.

As if to say, look, at the age of 85 I have struggled finally to bring closure to a story of the books in the library, that truthfully began in the ’40s. It just blew up in the ’80s, but it was an issue that was always undercurrent in the world of Lubavitch, if the library is a private library or is it public. The Rebbe struggled with that his entire life. Finally, at the age of 85, he turned around and looked and said, this is it. It’s finally come to a completion. His expression was, I’ve gotten nothing in this life easy. Nothing came to me easy. Joy was a work of his life, to bring happiness into his life.

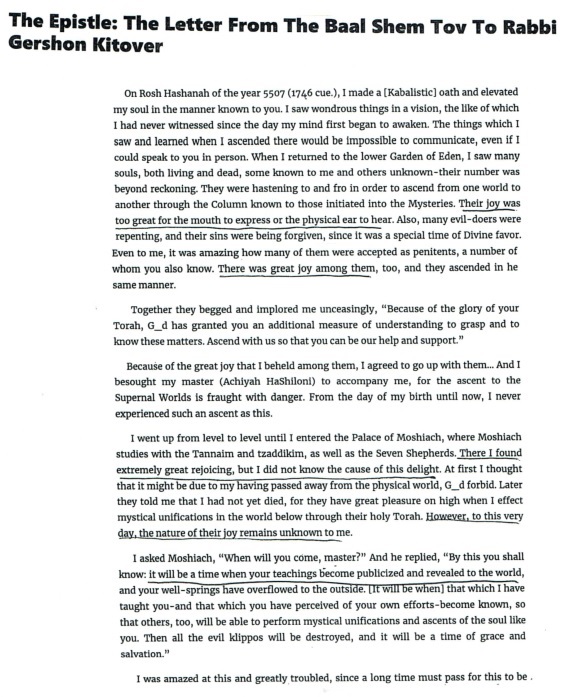

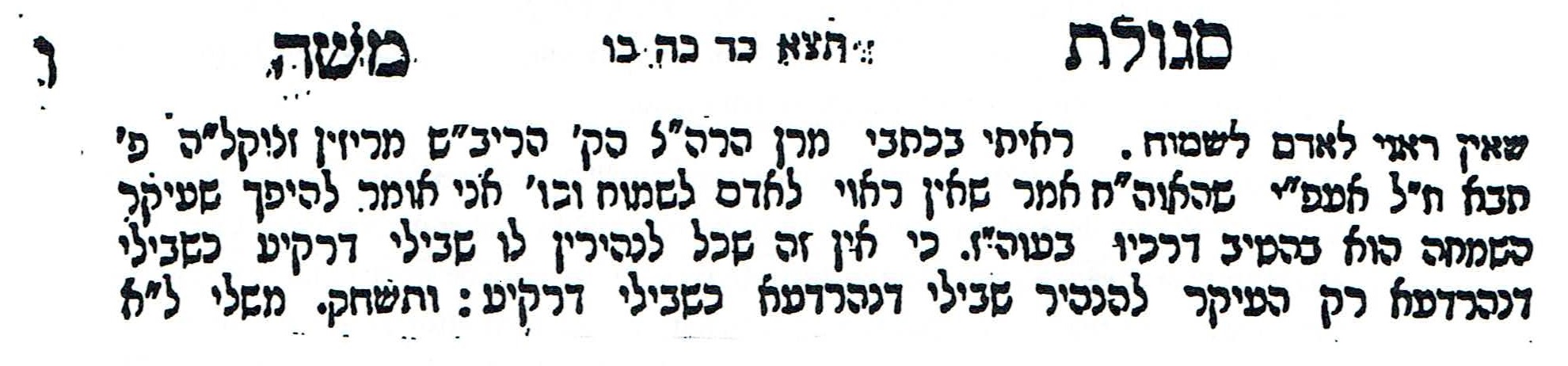

I want to show you something very interesting. I know that I don’t have the English translation. Forgive me. They recently discovered a little note that the Rebbe wrote, most probably to one of his secretaries. It was never really spoken about and it was never really, you know, but here goes the little note. The note is in Hebrew and I have made a copy of it. It’s right in my A. What you’re looking at is the Rebbe’s handwriting. It was most probably scribbled by the Rebbe on something written to him and he just scribbled on the bottom of it, for whatever purpose he scribbled the idea that he wanted people to hear. They recently discovered this note.

I’m going to read the Rebbe’s actual words and I’m going to translate it for you. Beneath it is from the script of the Rebbe to the Hebrew writing. “Kamah v’kamah p’amim,” multiple times, “bikashti,” I requested, “v’orarti,” and I asked and pleaded, “shebichlal,” to the collective community, “u’befrat,” and to the individual in the community, “bizman hazeh,” in our times, “tzarich lihyos b’simchah,” our times, the relationship of G d has to be with joy.

Now, listen to this. The Rebbe then adds this is the second line in Hebrew wording. “Muvan,” which then is self understood, “she’b’im hashaichim eilai,” those that are associated with me and have a relationship with me, “hu b’simchah,” they will be happy, “po’el zeh gam bi,” it will have an effect on me.

What an amazing little recent find of a handwritten note of the Rebbe. How the Rebbe says, I’ve spoken about this and I try to explain to people and urge people, that as a collective group of people, meaning the Jewish community and as far as individuals go. Today’s work is through joy. Judaism has to have a joyous tone to it. Then the Rebbe personalizes it. How does the Rebbe personalize it? The Rebbe says, those people that consider themselves close to me or connected to me, you should know that if you live in the joyous manner, how much it will affect me by the fact that the people associated with me are joyous.

So the Rebbe looked at the community, knew his struggle of being a joyous person, worked on himself and then pleaded with the community that as a way of life in the community, Judaism should be carried through joy. Then personally, the Rebbe says, I will be influenced by that as well.

So I want to speak about this concept of joy and I promise you that I’m going to come back to the Rebbe and talk to you about the Rebbe and how the Rebbe approached it. Because it’s not just simply, like I’ve said to you in the past, the Rebbe never approached something just okay, it’s the cool thing to do. There was a thought process to everything he did. It grew out of a history of a relationship of the Chassidic world, the non Chassidic world. The Rebbe had this whole complex reality in his eyes, what history spoke about a relationship with G d.

I want to walk you into it and start it out by telling you, that what is very obvious to the world is that the Chassidic movements are all immersed in joy. It’s one of our traits. We are known for this. You know, I was reading recently a great little story. The story goes as follows. The Griz let me tell you who the Griz was. This is the Soloveitchik dynasty, Rabbi Yosha Ber Soloveitchik of Boston. His father’s name was Rabbi Moshe. Rabbi Moshe’s brother’s name was Rabbi Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik. Rabbi Moshe Soloveitchik, World War II time right before World War II made it to the States and he became the Rosh Yeshivah of what we know today as Yeshiva University. Rabbi Soloveitchik, of blessed memory, from Boston inherited his father’s position when his father passed away.

Rabbi Moshe’s brother got out of Poland pretty late. It took a lot of work to get him out in ’41. When they finally got him out, they got him to Israel and that’s where he set up the Brisker yeshivah in Israel. In 1941 he was trapped amongst a lot of Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto. This is when Hitler was starting to implement his whole Polish plan. They ended up getting him out of the Warsaw Ghetto after the Yom Tovs and he was able. But for Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Sukkos, the Griz, Rabbi Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik, was in the Warsaw Ghetto. They smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto one lulav and esrog. That’s it.

The whole Warsaw Ghetto, whoever was in the Warsaw Ghetto, came by the line there was a line and everybody made a blessing on the lulav and esrog. Right before the Griz was on line amongst everybody, there was this Chassidic Jew from the Gerrer dynasty that stood on line and blessed the lulav and esrog and was dancing with the lulav and esrog. Then he put it down and gave it to the next person. The Griz was a little bewildered. Forgive me for saying this, but in the cold, intellectual, Lithuanian way of doing things, you don’t dance when you do things. You do it because intellectually you comprehend it and you appreciate it and it’s a serious moment. You don’t stand there dancing when you do it.

So the Griz was watching this man dancing with the lulav and esrog. So as he walks by he asks somebody, who is that man? So the person said, if I told you the story to him you won’t believe it. He says tell me the story. He says, after Yom Kippur, two days ago, the Nazis murdered his wife and three children and he was sitting shivah up to the Chag, until yesterday afternoon. But right now, was the mitzvah of blessing the lulav and esrog, he danced. The Griz turned around and said, only by Chassidim, only within the Chassidic world do they understand the concept of simchah shel mitzvah, how to have joy in doing a mitzvah.

The Chassidic world is connected to this idea. How do they get there? It wasn’t a simple thing. So let me walk you back a little bit and as I walk you back, we’ll understand it. You know, the coordination and organization of Lithuanian Judaism, which became the domineering force in traditional Judaism, was begun by the disciple of the Vilna Gaon, Reb Chaim Volozhiner, from the city of Volozhin. This famous disciple took the whole Lithuanian world and said we’re making a yeshivah world. Off of his perforce of power, to do what he wanted, became the five great schools of the Lithuanian world. Brisk, Mir, Volozhin, Slutsk and Slabodka great five schools that dominated the Lithuanian world, the yeshivah world.

In that yeshivah world, which was so disciplined about study, the little language that they talked about relationship wasn’t Chassidic language. They used a system called mussar. Messilas Yesharim, different writings of mussar, which, basically spoke about it wasn’t about the law of G d, it was about behavior. Because if you don’t behave, you’re going to get punished. In all that language of fear, that you have to do the right thing. They had these periods throughout the week, Shabbos, where they spent that hour they wouldn’t spend too much time either, because they didn’t want to take away from studying and learning.

They knew that they had to have, alongside study, they needed some kind of way of talking to them, not just simply what’s the law if an ox gores a cow. Or what’s the law of two neighbors sharing territory. That’s the study of Talmud. Or what’s the law of carrying on Shabbos. They needed a moral conversation with the kids. The moral conversation was mussar, that spoke to the students and this became its major running theology. Along the academia side was this whole awe and fear conversation.

The Chassidic world, walked in and started to carve out arm space at the table. In carving out arm space at the table, became this conversation of how to speak this moral language. It was not an easy thing to walk away from writings that were previously tremendously steeped in awe and fear of G d, reward and punishment language. They started to move, but it was a very slow movement. So I want to walk you into one of the first original movements. I’m going to show you that in the movement there was two sides. There was the side that, in many ways, didn’t speak about punishment, but spoke about the humility of the person, the lowness of the person. They didn’t go into the reward and punishment, like the mussar world went into. They stopped more to language which spoke about humbling the person.

It was the Chassidic way of speaking about the negative. It just spoke about how small you are. By speaking about how small you are, you are small. That’s it. You’re small, what are you doing? That’s how the Chassidic world moved away from the mussar language into the language which reflected a lot of the mussar ideas, but just didn’t speak about reward and punishment, it went into this language of the smallness of the person.

One of the original people to start this, was the Ba’al Shem Tov’s grandson. The Ba’al Shem Tov had a daughter called Odel. He had a son called Tzvi Hirsch, but he had a daughter called Odel. From this daughter called Odel was born a man by the name of Rav Boruch, who ultimately become known as Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz. He was the grandson of the Ba’al Shem Tov.

The disciples of the Ba’al Shem Tov, the old generation disciples of the Ba’al Shem Tov Reb Pinchas Koritzer, Reb Mechel Zlotchover, Reb Yaakov Yosef MiPolna these great people all spoke about how the Ba’al Shem Tov truly desired that this grandson should inherit the entire leadership. That the Chassidic movement should continue in a way the Ba’al Shem Tov, the Maggid, the Ba’al Shem Tov’s elder disciple. Then, when Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz, his grandson, will be ready, he should take over. The Chassidic dynasty should remain all united under one personality.

These elderly Chassidim of the Ba’al Shem Tov would tell a story. They would say that when this soul came down to this world, he didn’t want to come. He wanted nothing to do with this world, the soul of Reb Boruch, but they enticed him by saying to him he’s going to inherit the leadership of his grandfather. When he heard that, okay, I’m coming. That’s what they spoke about. But what happened was that many of the great disciples of the Maggid, the disciple of the Ba’al Shem Tov who inherited the leadership, created their own dynasties. Including the Lubavitch world, the Chabad world, Reb Schneur Zalman of Liadi. Including Reb Boruch Mezhibuz’s cousin, Reb Nachman of Breslov. Including Rabbi Elimelech of Lizhensk.

These were great people. Including Rebbi Nochum Tchernobeler. Including Rebbi Mendel of Vitebsk, who went to Israel to establish a Chassidic community in Tzfat. These were great disciples of the Maggid that didn’t fall into line behind the grandson, Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz. For years Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz resented the Alter Rebbe for that. He felt that the Alter Rebbe was part of those that led this radical new way of thinking, that you don’t have to have one Chassidic master, you can have multiple dynasties.

Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz sat on his grandfather’s lap, literally, I don’t mean that figuratively. He literally sat on the Ba’al Shem Tov’s lap and figuratively sat on his grandfather’s lap. There’s a sefer that’s called Butzina D’nehura Hashalem, which is recordings of Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz, his teachings. In the sefer you get a glimpse into his perspective. His perspective, the way he projects it, is his grandfather’s perspective. He’s very clear about that, that I’m talking as if my grandfather’s talking.

I made a copy and again, you’re going to have to forgive me throughout this whole class because the Chassidic world teachings have yet to hit Artscroll. Artscroll hasn’t said, oh, we’ve got to pick up on the Chassidic world teachings and start translating the stuff. Maybe one day they will, but right now Artscroll’s too occupied in the traditional stuff so they’re not translating these writings.

Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz writes like this it’s my B on Page 1. He says like this. I’m not going to read the Hebrew so it’ll go a little quicker. He says they asked my grandfather, what is today’s way of servicing G d? We’ve known from previous writings of previous generations that the way people service G d was by fasting from Shabbos to Shabbos. But you have spoken publicly that you have decided that that’s the wrong way of servicing G d and if it’s the wrong way of servicing G d so then what’s the right way? You actually said that it’s a sin to service G d by fasting the entire week. So tell us how should we service G d.

So again, steeped in the writings of mussar was fasting. Now, the Ba’al Shem Tov came out and said don’t fast. So the Ba’al Shem Tov responded to his grandson, I’ve come to this world to show a different way of how one has to fear G d. The way I want to teach you is that it’s connected to loving G d, loving his Jewish people and loving the Torah. Therefore, the way to do that listen to this is to break the relationship with physicality. You’re going to eat. Eat because you have to do a mitzvah, not because you enjoy food. Don’t have a relationship with it. So go ahead and eat, but when you eat behave as if you don’t enjoy it. With that you break your evil inclination and with that you take and you break the spiritual energy in the food away from the ta’avah, from the pleasure, the materialistic pleasure.

This is the grandson turning around and explaining how he believes the Chassidic movement has to go. The way he spoke about how the Chassidic movement has to go is very simple. We’re not into fasting anymore, but we’re into humility, humble. Don’t behave luxurious, don’t behave comfortable. Oh, you’re an uncomfortable person in this world. That’s the flipside of what the Lithuanian world was speaking about reward and punishment. It’s the uncomfortableness. So there you go. There was no conversation of really joy. The conversation was about humility, humbleness, bittul, self nullification.

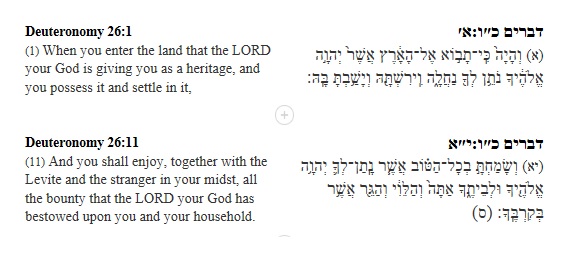

I want to show you the flipside. The flipside was a disciple, the same time as Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz. The same class. Disciples of the Maggid, the Ba’al Shem Tov’s student, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok of Berdichev. Rabbi Levi Yitzchok of Berdichev, on the portion of Chukas, goes into a great explanation about a major debate between Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki and Nachmanides on what was the story behind the hitting of the rock of Moses. Again, I’m not going to read this to you, but it’s my C, beginning on the bottom of Page 1, going on to Page 2.

That the Berdichever says they argue. One says that the problem of the story of hitting the rock wasn’t about hitting the rock, its was the fact that Moses spoke harshly to the Jewish people. Lost his cool. The other says, no, it’s not about he spoke to the Jewish people, it’s more about the fact that he hit the rock. The Berdichever says, I want to explain to you that they’re not really arguing. It’s the continuation of one idea. What’s the idea? He says there’s two types of leaders. There’s leadership where the purpose of what you want out of the community, what you believe the goal of G d and the community is, is rebuking them. You spoke to them of how they have done wrong. How they’re losing a relationship of G d. If you don’t give them this you’re hurting Him. Harsh language.

Then there’s leadership that speaks to them about their relationship with G d. How G d loves them and how G d desires and how everything they do for G d is a blessing. It’s through the teshukah, it’s through bringing out within a person that love, that connects the person. The Berdichever turned around and said I want to tell you something. G d expected Moses to create that relationship through love. He didn’t do that at this moment. He turned around and went into speaking to the Jewish people rebuking them. Because of that, he showed them what rebuking is about. It’s about nullifying the physical. He hit the stone.

G d said, no, that’s not the type of leadership I want. A leadership that I want is not through rebuking and destroying, overwhelming the finite world by nullifying it. I want one who brings out love. I want one who brings out joy in what you’re doing in a relationship with G d. Also, the Berdichever, in this beautiful language he was a major thinker challenged the whole Lithuanian world and translated the story of hitting the stone into a very real conversation about what was taking place then. What’s the relationship that you need to have with G d? And as a leader of a community what are you asking from the community, what kind of relationship the community should have?

He was willing to go to the point and say that let me tell you something. These two relationships are at the center of why Moses didn’t go into the Land of Israel. That Moses thought maybe the relationship has to be through rebuking and through showing that the relationship with the world is by breaking it. Hit the stone. G d turned around and said, no, that’s not the type of relationship I want. So he took this great story and brought it right up to current, at the time when the Chassidic movement and the Lithuanian movement were struggling in trying to find its feet. Then, in addition to the world of academia, what’s the moral message and the morale message of how people should live by, in addition to their knowledge? What’s the style of life you’re asking of people?

The Berdichever turned around and said, let’s go away from that, rebuking. Let’s go away from that type of language of breaking the world. Let’s go into the language of a relationship with G d, of joy. All of a sudden, you started to hear two people. Both of them present with the Maggid, the Ba’al Shem Tov’s disciple. Both of them well aware of the Ba’al Shem Tov. This was their moment in life. Challenging each other of the direction of the Chassidic movement.

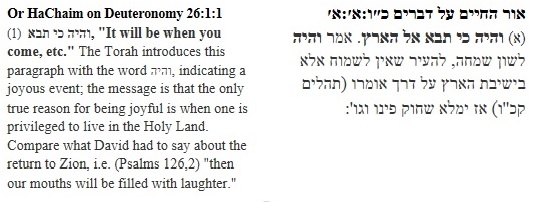

Let me keep on moving you, because this is going to give you an insight. I want to walk you into the next, which is my D on Page 2. It’s a great, great, Rabi Zusha of Anipoli. Reb Zusha of Anipoli all these people lived in the late 1700s to the early 1800s. This is the timeframe of Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz, this is the timeframe of the Alter Rebbe, this is the timeframe of Rabi Zusha of Anipoli. He wrote a sefer, a beautiful book called Menoras Zahav. Rabi Zusha of Anipoli, his brother was Rabi Elimelech of Lizhensk, two famous brothers.

Rabi Zusha, by the way, if you look at the Tanya, the Lubavitcher Alter Rebbe’s writing of Tanya. The haskamah, one of the letters of acknowledgement and recognition for this book is Rabi Zusha of Anipoli. He gives a letter of reference, so to say, on the Alter Rebbe, in the intro to the Tanya.

Rabi Zusha takes a beautiful verse that we know, because we say it in bentching. The verse goes, “Hazorim b’dimah b’rinah yiktzoru, “those that sow in tears will reap with song and joy. “Haloch yelech u’vacho,” those who go along weeping, will end up carrying the seed back. “Bo yavo b’rinah,” he shall come back with song and joy, he will carry the sheaves. This is the Shir Hama’alos. Now, you’ve got to follow along. It’s just two lines, but follow along with me, it’s a beautiful writing.

“Hazorim b’dimah,” there are those people who have a relationship with G d this is Rabi Zusha of Anipoli b’dimah, through tears, embitterment, brokenness, broken hearts, humble. Then are those that have a relationship b’rinah, with joy. You should know, both of them yiktzoru, they’ll both reap. Both will have reward, will see what they have accomplished. Both systems, he says, have value. Those that sow with tears, those that do it with joy, yiktzoru, they both will see their fruit of their product. But, he says Verse 2 “Haloch yelech u’vacho,” those that go with tears, embitterment and broken heart, humility, “nosei meshech hazora,” will come back with a bag. “Bo yavo b’rinah,” those that will go with joy, “nosei alimosav,” they’re going to come back with sheaves and an abundance.

Rabi Zusha of Anipoli’s way of saying he says, of course, you’ll see benefit from the bitter relationship and broken and humbleness. But I’m telling you, if you want to see an abundance now, you can translate this abundance in multiple ways. You can translate to the individual, that the individual will have an abundance of a relationship that comes through embitterment. Or you can talk about the whole Jewish community, that it’s only to a selective part of the community that in a bitter relationship translates. You want to talk about an abundance, you want to reach the greater community? The only way to reach the greater community today this is what Reb Zusha of Anipoli was saying then. The only way you reach the greater community today is only through joy.

Off color, off record no, I shouldn’t say off color. Never off color. Not of subject either, by the way, very much on subject. There’s a Mishpacha magazine. It’s a magazine that comes out from the Orthodox world. I don’t get a copy of it, but it’s out there. Recently there was an entire debate. Because there’s a man by the name of Rav Moshe Weinberger, who is the Chassidic teacher in YU. Yeshiva University, the great Lithuanian school, hired like we would say in the Chassidic world, a mashpia, a spiritual leader. His name is Rav Moshe Weinberger. He has a shul, a big synagogue, in Lawrence, New York. He’s a YouTuber, Moshe Weinberger. He’s a brilliant speaker. He’s a Chassidic Jew. He speaks a beautiful English and he’s reaching an unbelievable crowd.

He, basically, wrote an article in the Mishpacha magazine, which the article was how far reaching mysticism and Chassidus has gone, that it’s affected everybody. Comes along a rabbi from Baltimore, Maryland, the Ner Yisroel world, one of the great Lithuanian houses of study. I think his name is Shafran. He writes an article and says what are you talking about? We have a way without mysticism and it’s booming and beautiful. Why do you say that without mysticism? Comes back a third article, by an entirely different writer. His name is Sifram, Sifton (ph). You look it up in the Mishpacha magazine. He comes back and says, my dear friends, the war is over, they won.

He comes back and writes a whole article. Let’s stop it. The spirit of Judaism today is being carried in the mystical voice and it’s permeated every single it’s brought joy and feeling into what we’re doing. He goes through how the Carlebach synagogues, how the minyanim throughout every neighborhood that has Friday night singing and dancing. It’s not Chassidic Jews, it’s Lithuanian Jews that simply want to find the joy in why their doing it. Because the simple academia is not translating itself to people on a morale level. The spirit is not there.

This is exactly what I just read to you from Reb Zusha of Anipoli. Reb Zusha of Anipoli turns around and says I agree there’s a zorim b’dima, there’s the concept of embitterment and knowing what’s right and wrong and knowing how small you are for the sins that you do. And have in mind the fact that you’re a sinner. But at the same time, I want to tell you, there is b’rinah, there is the way of servicing G d with joy. I’m telling you, Reb Zusha says, that to the masses, the sheaves is joy.

There might be the select few that gather more bags. They appreciate the awe fear and the concept of humility. It doesn’t speak to the masses. This is a writing of Reb Zusha of Anipoli in his sefer Menoras Zahav. At that time in history, he parked himself right in the camp of that the whole purpose of the Chassidic movement is to move the movement and to move Judaism into joy.

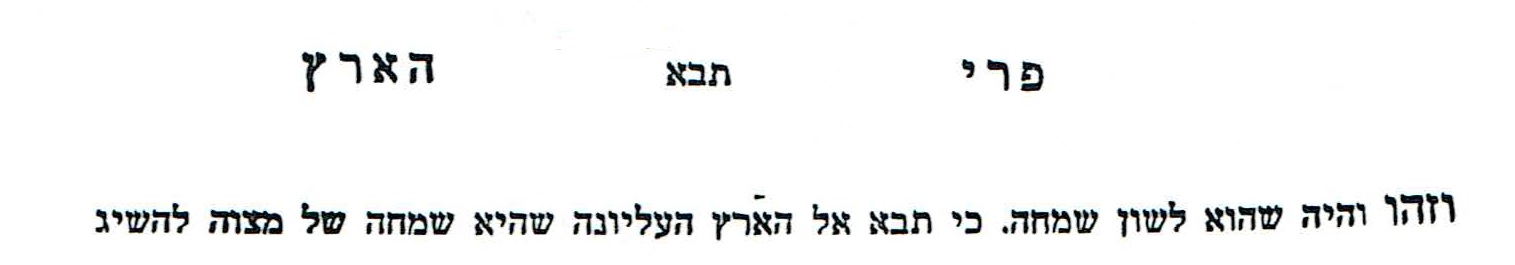

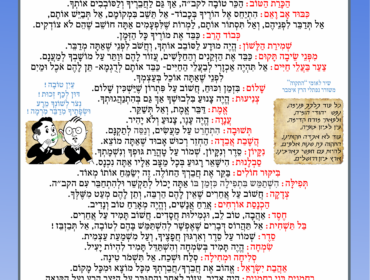

Flipside. Because this is what we’ve got to do. We’ve got to show you that it wasn’t that simple. At that same time, in the same era late 1700s, early 1800s a disciple of the Maggid, part of that whole group of followers, there was a man by the name of Reb Moshe Sassover, from the city of Sassov in Galicia. He wrote a book or the students wrote a book, called Likutei Ramal. You can see those large letters on my page and it’s in my E. Likutei Ramal is an abbreviation for Reb Moshe Leib. That was his name, Reb Moshe Leib Sassover.

In the opening of his writings, he picks on a Midrash Tanchuma, which I for this I found for this I’m going to give you the translation. A beautiful Midrash Tanchuma. Right in the opening of the Midrash Tanchuma, 1:1, the beginning of his writings. The Midrash says like this. That when G d created the world, it’s like someone who builds a building. So what was the blessing G d made over the creation of the world? An interesting question. It’s not about G d only, he’s asking about people that build houses. So the blessing you make is, “Shehecheyanu, k’dei sheya’aseh nachas ruach l’Yotzro,” thank You for giving me this new thing that I can just simply please G d.

This is what the Midrash Tanchuma speaks about at the moment of creation, when G d created the world. It’s as if, what’s the blessing on the creation of the world? The blessing is, “Shehecheyanu, k’dei sheya’aseh nachas ruach l’Yotzro.” He must recite this prayer in order to please his Creator. Reb Moshe Leib goes into great length saying, listen, that a core existence of creation is nothing more than G d. Period. There’s no joy for you, there’s no purpose for you. It’s simply one purpose, G d’s joy. If for one second you think somehow or other this existence is for you, you’re making a horrible mistake. The only way you’re going to come to realize that it’s G d’s joy, is humble yourself.

He goes into language and at the core of his language is that a person has to understand, he has to be in pachad, he has to be in fear. He has to say to G d, “Mah asisi? Lo asisi klum,” I’ve done nothing. “Mah ani,” what am I? “Mah chayai,” what’s my life? “Shafal enosh k’moni,” such a low person like me, “l’daber,” to even speak to you. Humility. This is one of the founders of the Chassidic movement that, again, didn’t go into reward and punishment like the mussar world, but it’s the flipside of it. What’s the flipside of it? Humility. There’s no mention of joy, that the core reason why G d created this world is somehow or another we should be happy. No.

Audience Member: But doesn’t this show a graduation between ourselves and G d, meipachad l’ahavah?

Rabbi Alter Bukiet: He doesn’t say that.

Audience Member: But does he imply that?

Rabbi Alter Bukiet: He doesn’t imply it at all. His implication is very simply that the core reason why we are here in this world is simply to bring out G d’s will and the way you can only do that and that’s the brachah we make, so to say, G d’s making at the creation of the world. That it’s simply for G d. Then he helps you understand how you do that and it’s all about humility and it’s all about humbleness. This is a Chassidic master. Okay?

I’m going just tell you a couple of others, just to walk it without the paperwork here, because I knew I’m going to run out of time and I didn’t want to make multiple sheets. At the same time just to give you an insight to this on the flipside. I want to take you to a generation later than the Chassidic movement. I want to move you now, you know, to the early 1800s, to the mid 1800s. There was Reb Yitzchok Yaakov of Peshischa. He was a disciple of Rabbi Yitzchok Yaakov of Lublin. He was a fellow friend of the Kotzker. He was the next generation, I would say the fourth or fifth generation of the Chassidic movement.

He came out and said like this. I want to tell you something. That Moshiach is only going to come through the service of joy. I’m telling you now, he says. If you believe that the Chassidic movement is the pre Messianic era movement and you believe that this is ushering in the Messianic era, this movement. Let me tell you, at the core of this movement has to be joy. You’ve got to focus people on joy. That’s the only way you’re going to do it. He turned around and he said and then he used very nice language. He said before Moshiach’s going to arrive, you know how people are going to be? They’re going to be dancing in the street. Not because they know Moshiach has arrived, but that’s going to be the type of service.

Which reminds me so much of what Chabad will do. They will take the joy out onto the street, public. That’s the language he spoke. He faced his community and he said, listen. We have to teach people to live through joy. The flipside to it. Same time. So a great Chassidic master, Reb Chanoch Henech of Alkesander. He was a Kohen; his last name was Levin. He lived until 1870.

In the Chassidic dynasty of Ger, the great Polish Chassidic dynasty, there was a gap space between the first Rebbe and the second Rebbe. Reb Itche Meir of Ger, who was a disciple of the Kotzker, when he passed away, his son didn’t want to be Rebbe. It’s his grandson, Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh Leib of Ger, that became the second Rebbe. There was period in between until the grandson. In that period Reb Chanoch Henech of Aleksander, who was a disciple of the Kotzker. A lot of people went to him until the second Gerrer Rebbe became Rebbe. I know this because my family comes from Ger, so this is part of the history.

Reb Chanoch Henech of Aleksander spoke tremendously about the concept of merirus, embitterment. About broken heartedness to G d. But at the same time when he spoke about that and it’s an amazing language of his, he was so into it that he was nervous. He spoke about it frequently that you’ve got to be careful that from embitterment and broken heartedness, it’s very easy to cross over to depression. If you don’t know how to gauge it you can depress yourself. He is one of those that started to talk about depression as a problem behind the way of approaching G d through brokenness. That if one doesn’t know how to gauge it properly.

So you don’t see people who are joyful depressed. It’s not one of the symptoms of a joyful guy, oh, he’s probably depressed. No, he’s not depressed, he’s a happy person. Unless it’s totally a false type of happiness that he’s hiding behind. Usually a truthfully happy person is not a depressed person. A brokenhearted person, if it’s not done properly and if people try and become brokenhearted and don’t know how to, the line to depression can very and therefore, Reb Chanoch Henech of Aleksander worked very hard on trying to separate between merirus, embitterment and atzvus, depression.

Now, if his work in life was joy, he wouldn’t be a therapist trying to help people understand how don’t cross the line from embitterment into depression. That wouldn’t be a conversation. I’m demanding of you joy. Go away from bad thoughts. The fact that he had to go there is a proof that that’s the territory he was hanging out in. That was the world that he was working on, how a person should be brokenhearted, merirus. A person should be humble. Well, when you go down that line and it’s not done right, it can end up with tremendous problems. Therefore, all of a sudden, he was swinging the story to the other way, but I don’t want you to fall into depression.

This is 1870s. We’re not talking about 1812, this is the next generation of Chassidic thinkers that went into this whole conversation and struggling to know what’s the person of the Chassidic movement. Is it joy or is the Chassidic movement a movement that the moral conversation is broken heartedness, humbleness, humility? Are you all following along with me so far? Good.

I want to walk you into the Chabad world and that’s my Page 3. Now, you know, I know I’m an hour into the class, so I don’t know if I’m going to do everything inside. Forgive me because, again, I’m just running behind time. But I want to walk you into this because it’s the Rebbe.

The Rebbe, in a Chassidic discourse, in 1986, Shabbos Parashas Vayishlach, said a beautiful discourse. It’s in the middle of the Chassidic discourse, so to a certain degree, I’m not going to bring you into the whole conversation. I’m going to detach this idea what the Rebbe spoke about and try to present it to you independent and insert it into our conversation, because it’s highly important. It’s a beautiful Chassidic ma’amar. The Rebbe said Taf Shin Mem Vav, I think Kislev. Maybe it wasn’t yet 1986, maybe it was still 1985, but Taf Shin Mem Vav on the Jewish calendar, in the portion of Vayishlach. Margele b’pumei d’Rava, that’s the name of the Chassidic discourse.

The Rebbe says like this. I’m going to tell you the radical line the Rebbe says later. Let me get you to the radical line. It’s not radical. It’s the Rebbe and I go back to how I present it the beginning, but let me just get you there. The Rebbe starts explaining to you the Alter Rebbe’s position. The Alter Rebbe parked himself in the middle of these great personalities that I just told you all about, same timeframe, because the Alter Rebbe lived from 1745 1813. He was right in the middle of all these original thinkers. Reb Boruch of Mezhibuz that we spoke about, Reb Zusha of Anipoli, Rabi Levi Yitzchok of Berdichev. All those different great thinkers that were struggling with embitterment versus joy. The Alter Rebbe walks straight into it.

The Alter Rebbe says in Iggeres Hateshuvah, his writings on repentance, Chapter 11, is based on these two ideas, but he approaches entirely differently. He speaks about it through repentance. The Alter Rebbe goes into it like this. The Alter Rebbe says there’s two levels of repentance, there’s teshuvah tata’a and teshuvah ila’a, the lower level of repentance and the higher level of repentance. Simple language the repentance that’s done in the most obvious way, you’re a broken person. You did wrong, you sinned and you’re asking for forgiveness. It’s all about brokenness.

Then there’s a higher level of repentance which reflects, not so much on the fact that you’re distanced from G d and it’s about the fact that you’ve done wrong. It’s about a relationship with G d. It’s about a feeling of joy for G d. It’s like a child who dances to do something for his parent and in doing that for the parent, the parent forgives him for everything. Because the parent sees the joy that the child has in having a relationship with him. In that joy, that sheer bond, everything is forgiven. So one who’s distant, needs to feel brokenhearted that why am I distant? How did I lose a relationship? That’s the lower level of repentance.

The Alter Rebbe says, which basically, in different language, it’s the two ideas we’re speaking about until now. One idea is that you focus on the fact that you’re not one with G d and therefore, you’re humbling yourself. How can I distance myself from G d? Who am I to distance myself? What am I? How did I allow myself to become a person like this? The Alter Rebbe says that type of relationship, you shouldn’t do it daily. Pick a time to do it. The Alter Rebbe speaks about doing it at Tikkun Chatzos, waking up at midnight, you know. But during the day don’t live in that. Or the Alter Rebbe speaks about doing it on the eve of Shabbos, before the week comes to an end, but don’t live in that brokenness the whole time.

He says, no, I don’t want you to live there. Where do I want you to live, the Alter Rebbe says, in joy. Meaning, in the fact that you have a relationship with G d, that G d’s your parent. G d loves you, G d wants you. Teshuvah ila’a, the higher level of repentance, where it doesn’t come out of distance. It comes out of to the contrary. It comes out of the fact that you know what? There’s a relationship and because there’s a relationship there’s joy and desire and feelings are flowing. That’s the Alter Rebbe.

The Rebbe jumps on it. The Rebbe says I want to start with my premise based on the Alter Rebbe. Therefore, the Rebbe says, I want to tell you something. That I accept the Alter Rebbe’s premise that we should be a generation of people that predominantly needs joy. That’s how you have to live. Because there’s joy and that’s the type of repentance that a person does because he senses a relationship, don’t speak about negativity, don’t mention it. Then the Rebbe adds an unbelievable line. I’m not yet at the punchline of the Rebbe, I’m leading up to it. An unbelievable line.

The Rebbe says, as a generation listen to this as a generation, the merirus, the brokenness and humbleness we have experienced already. That part of a relationship with G d where G d humbles us and we are humbled, we got it in Spain, he said. We’ve got to move to the next level of the relationship where it’s all about joy. The joy comes, like, from the concept of repentance of the higher level of repentance. What’s the higher level of repentance? The higher level of repentance is that G d desires a relationship.

Then the Rebbe says I want to turn this thing one step further and this is the amazing part of this Chassidic discourse. What’s the one step further? You see, all these great mystics and the Alter Rebbe included, that spoke about joy, it all was some form of a relationship. You had to do something to experience the joy. So from their perspective go ahead and do mitzvos. Sit and learn. Because that’s going to bring out the joy. What else is going to bring out the joy? That’s the joy. All right.

The Rebbe turned around and says no. I want to go one step further, the Rebbe says. You want to know where the real true joy comes from? It’s not through the system which all the other mystics spoke about, which the system is all how G d is in a relationship with you. How do you know that? Look at the system. G d wants you to do this, therefore, He’s enjoying you. You’re doing it; therefore, you’re getting joy out of it.

The Rebbe says I want to go one step further. The true reason why our generation should be in joy is for a whole different reason, which puts everybody else’s joy into a secondary position. The Rebbe’s reason for joy is because the essence of the Jewish soul. Period. End of conversation. Because you have an essence of the Jewish soul, that essence of the soul, it’s not you need a system to make it one with G d, it is one with G d. You need to have a system just to reveal it.

It’s like, for example, a person has furniture in his house and you turn on the lights. What’s the real reason why you want to be in the room? It’s for the furniture. The dining room table, you want to eat. The couch, you want to sit and relax. If I didn’t have lights I wouldn’t know where the table was, I wouldn’t know where the couch is. Therefore, I put on lights. So the light helps me to see. But who walks into a room to say, you know why I’m coming into this room? My whole purpose is light. I don’t need furniture, I don’t need a dining room table. The fact that there’s light in the room, now I can stand there and I’m fine. What’s fine? Well, what’s the beauty of the room if I have no the only reason why you have lights is to reveal what’s in it.

The essence of the soul of the person is the furniture. The Torah and the mitzvos is the light. That’s how the Rebbe views it. Therefore, the real joy is not the fact that there is a light that reveals the furniture. The real joy, to the Rebbe is, that essence of the soul. You need the Torah and mitzvos that turns on the light in the room. That now you see what in essence you are. But not that that’s creating who you are. It’s there. Therefore, the Rebbe turns around and says, you want to talk about the real joy? Is that a Jew has to realize what in essence he is. Period. That’s our generation, the Rebbe says. In our generation, the way that we’re going to reach a Jew is not talk to him about the lights. Start talking to him about the essence of his being.

He wants to experience the richness of the couch, he wants to experience the richness of the dining room table, get a light. But what are you really experiencing? Something that’s essentially there and it’s not part of the system. It is who you are. The Rebbe says this is the generation that will be, to a certain degree, stripped away from all those we’re in America, this great country. We’re not shtetl Jews. The reality of what our existence is going to be, because we’re going to bring out that essential bond, that in essence we’re Jewish. That’s the core of who we are.

I’ve said this multiple times. You approach any Chabad Rabbi and ask him what’s the greatest compliment that somebody can pay you after he walks into his Chabad House? Is it beautiful services of davening Friday night? Was it the great class? Or simply a person says to him, you know what? I felt at home, I just felt at home. Yeah, it was a nice class. Yeah, they were nice services. I just felt at home. That compliment is the greatest compliment. The class and the services are just to have the light switch go on and once the light switch goes on it’s just there to make the room a place where the person is comfortable in who he is. Period. People don’t know how to express it, but they say it. But it’s very simple, I just feel at home.

What did the Rabbi talk about? Who cares. Who davened for the amud? Who cares. It’s just my neshamah feels at home. This is what the Rebbe tried to accomplish. The beauty of a Chabad House, what the Rebbe tried to accomplish, was not that the Chabad House is a place where there’s a good minyan. Not that the Chabad House is a place, oh, it’s the great academic studies of Judaism. Of course, we do that and of course there’s a good minyan, but the essence of the purpose of a Chabad House is that the soul of the person is at home. It can come through people sitting across from each other and schmoozing about the biggest na’arishkait.

It makes no difference. It’s just now, my soul has found itself in its most natural reality. That was the Rebbe’s goal. Therefore, the Rebbe said, that is the true joy. It’s not the joy that you bought a nice chandelier. That G d gave you a system. It’s the joy in knowing that you have the ability within the essence of your being to just be at home with G d in the most natural way, just by your existence. This is how the Rebbe translated joy of Judaism today. And this is how the Rebbe worked so hard on trying to identify what he believed, throughout the whole richness of the Chassidic world of how they present the joy versus embitterment, et cetera, et cetera.

The Rebbe came to this idea and presented joy through the greatest teachings of his life and presented it beyond any other teacher. Took it to a level where he knew what everybody else was teaching and he knew what his great great grandfather was teaching. But he took it to an entirely different level.

Have a good day, everybody.

(END RECORDING 01:04:27)

CERTIFICATE OF TRANSCRIPT

I, MOSHE GOLDBERG, as the Official Transcriber, hereby certify that the attached transcript labeled: REBBE’S VISION JOY A WAY OF LIFE (RABBI MENACHEM MENDEL SCHNEERSON CHABAD LUBAVITCH) was held as herein appears and that this is the original transcript thereof and that the statements that appear in this transcript were transcribed by me to the best of my ability.

MOSHE GOLDBERG

October 22, 2018

Transcription for Everyone

| Category | Judaic Studies, Religion |

| Tag | Adult Education, College/University, Homeschool, Informal Education |

Write a Review

Leave a reply Cancel reply